This article originally appeared on Inside Climate News, a nonprofit, non-partisan news organization that covers climate, energy and the environment. Sign up for their newsletter here.

EL PASO, Texas—On a Tuesday afternoon in May, earth system scientist Thomas Gill was tracking yet more dust rolling through this border city.

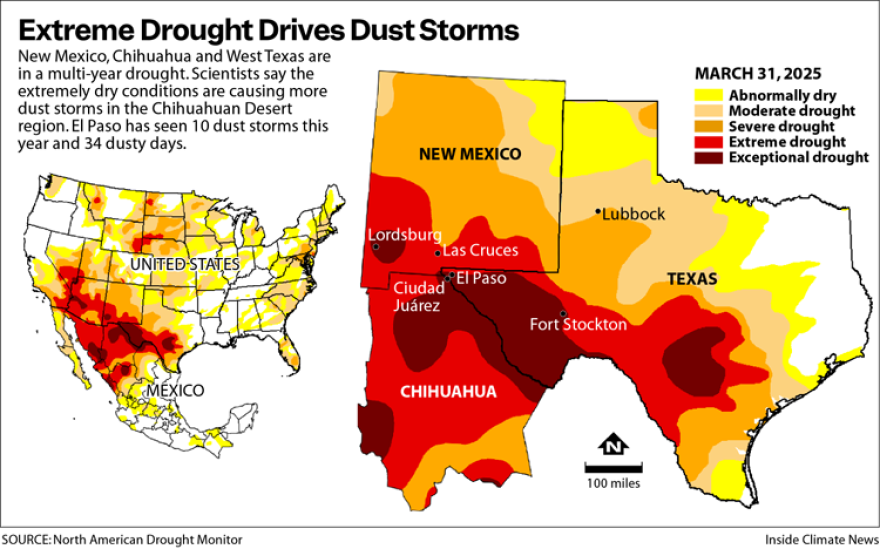

Gill, a member of the faculty at the University of Texas at El Paso (UTEP), was waiting to see whether this dusty day would swirl into a full-blown dust storm, in which visibility is less than a half-mile. El Paso has experienced 10 dust storms this year, trailing only the Dust Bowl years of 1935 and 1936. The average is 1.8 storms per year, according to Gill.

There have been dust events on 34 days this year in the border city, the highest total since 1970-71. Gill has been fielding calls from reporters around the country as dust blows from West Texas as far as Des Moines.

The combination of a windier than average spring and extreme drought in the U.S. Southwest and Northern Mexico have created exceptionally dusty conditions. High winds lift loose, dry soil and sand, creating dust clouds that travel long distances. Much of the dust blowing into El Paso comes from Southern New Mexico and Chihuahua, including from dried lakes known as playas. With little rain in the forecast, the dust conditions show no sign of stopping.

Airborne particulate concentrations have soared to hazardous levels during the storms, impacting local health. Exposure to particulate matter pollution is linked to aggravated asthma, decreased lung function and heart attacks in people with heart disease. Dust means closed highways, cancelled sports events, deadly car wrecks and increased hospitalizations.

Residents of the Borderland region, including El Paso, Las Cruces, New Mexico and Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua, are accustomed to dust storms. But Gill said this year is different.

“We’ve thought of the dust as a nuisance to people’s lifestyle in the Borderland, but not something that’s going to affect their activities,” he said. “I think it’s gotten bad enough this year that people are realizing it does have consequences.”

Extended Drought Drives Dusty Conditions

Dust storms occur around the globe, from China to the Middle East to North Africa. In the United States, they are most common in the Great Plains and desert Southwest. Drought is a key driver this year. The entire state of Chihuahua, which borders Texas to the south, is in drought, as are Southern New Mexico and West Texas.

Gill said typical dust sources like the Lordsburg Playa in Southern New Mexico have been active this year. But he said a “tremendous dieback of native vegetation” is contributing to dust blowing from new sources. Cattle are so starved for water and forage that they are dying on ranches in Chihuahua.

“In its natural state, the Chihuahuan Desert has a lot of grassland in it,” he said. “That grass is dying off and exposing a lot of bare soil and land.”

Texas state climatologist John Nielsen-Gammon said the current Texas drought, which began in late 2021 and early 2022, is longer-lasting than the short, intense droughts of the past few decades. Between 2022 and 2024, drought caused $10.9 billion in damages in Texas, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

“This is actually looking like the beginning of the 1950s drought, where we had lots of dry conditions that built on itself,” said Nielsen-Gammon, a professor of atmospheric sciences at Texas A&M University.

That drought, spanning 1949 to 1957, was more severe than the 1930s drought connected to the Dust Bowl. It devastated agriculture and ranching across Texas and kickstarted the state’s modern era of water planning. President Eisenhower visited the West Texas city of San Angelo in 1957 to survey the damage.

Gill said that 1950s dust events were severe and lasted much longer than they do today, referring to National Weather Services records. One West Texas farmer told Texas Monthly decades later that chickens and turkeys died during the 1950s dust storms from inhaling so much dust and dirt.

“I don’t think anyone would want to relive the dust levels of the 1950s,” Gil said. “The old timers in West Texas, they call the 1950s the ‘filthy 50s’ because of how dusty and dirty it was.”

The Chihuahuan Desert receives most of its annual rainfall during the summer monsoon season. July, August and September are the months with the most precipitation.

“What we really need is a good, really extensive, really wet monsoon season,” Gill said.

This year’s dust storms are coming on the heels of El Paso’s two hottest summers on record, 2023 and 2024. Nielsen-Gammon said that higher temperatures in West Texas increase the rate of evaporation from soil. This creates more dust that comes loose in windy conditions. Temperatures are expected to continue to rise with human-caused climate change.

Nielsen-Gammon cautioned that an extended drought will inevitably mean more dust.

“If things are dry enough for long enough, then we could see a lot worse dust than what we’ve seen in our lifetimes,” he said.

Dust Storms Create “Scary” Air Pollution

Dust storms send air pollution levels soaring, jeopardizing public health. Air quality monitoring stations in El Paso have recorded particulate matter levels several times the federal Environmental Protection Agency’s daily limit. Public health officials recommend staying indoors during dust events or wearing an N95 mask when outdoors.

Particulate matter with a diameter of 2.5 micrometers or smaller (PM2.5) can enter deep into a person’s lungs and bloodstream and cause the most damage. PM2.5 levels have rocketed past the EPA limit of 35 micrograms per cubic meter of air over a 24 hour average during this year’s dust storms. During one dust storm on March 3, PM2.5 was over 1,000 for two hours at one El Paso air quality monitoring station.

“That’s a scary number,” Gill said.

Most dust and sand particles register as PM10—particulate matter that’s 10 micrometers in diameter. The EPA’s limit over a 24 hour average for PM10 is 150 micrograms per cubic meter. The hourly levels of PM10 in El Paso’s air have exceeded 1,500 micrograms per cubic meter, or 10 times the daily limit, on 19 days this year, according to Gill.

In a 2021 paper, Estrella Herrera-Molina, who earned her doctorate at UTEP, found increased hospital admissions in El Paso for conditions including coronary artery disease and Valley fever after dust events. Valley fever, or coccidioidomycosis, is a respiratory infection caused by a fungus found in dust. Researchers are studying the connection between dust storms and Valley fever transmission.

“We still don’t have models developed as a society to address this,” said Felipe Adrian Vázquez-Gálvez, who oversees atmospheric sciences and green technology at the Autonomous University of Ciudad Juárez. “Maybe we should add this to the list of extreme meteorological events.”

Vázquez-Gálvez, who previously led Mexico’s National Meteorological Service, said that many people miss work because of respiratory ailments and allergies during dust events. He said this is especially challenging for non-salaried workers in Juárez who depend on daily earnings.

He has noticed that one air monitor located in a Juárez neighborhood with unpaved roads and heavy traffic often records some of the highest levels of air pollution in the entire country.

The dust storms show no sign of letting up. A paper in Lancet Planet Health in January warned that sand and dust storms are expected to increase globally because of climate change. The authors called for “international, collaborative, and multidisciplinary health studies” to better understand these storms.

NOAA researchers Bing Pu and Paul Ginoux used climate models in a 2017 paper in Scientific Reports to project changes in dustiness in the United States. They forecast that the frequency of dusty conditions would increase dust events in Texas.

Vázquez-Gálvez said long-term planning is needed to mitigate the impacts of both drought and dust storms. “Even if the drought ends this year, we still know there will be other droughts in the future,” he said.

Restoration Aims to Mitigate Dust Impacts

“We are witnessing the 21st century North American Dust Bowl,” said Mike Gaglio, the owner of High Desert Native Plants in El Paso.

Gaglio, a rain harvester and desert landscaper, has a front row seat to the dust barreling through the region on his twice-weekly drives between El Paso and the Lordsburg Playa. Since 2016, he’s worked on a project with the New Mexico Department of Transportation (NMDOT) to mitigate dust through ecological restoration at the playa.

Interstate highways are particularly dangerous places when a dust storm hits. Where Interstate-10 crosses the Lordsburg Playa, 21 people have died in crashes during dust events and the highway has been closed for safety 39 times since 2012, according to NMDOT.

Overgrazing has stripped the land, managed by the New Mexico State Land Office and the Bureau of Land Management, of vegetation. This leaves ample dust and sand to blow.

“Cattle grazing in the arid West is a big ecological disaster,” Gaglio said.

He and other partners have developed a process of plowing and then creating indentations in the soil to prevent run-off before seeding native drought-resistant plants like blue and black grama grass. Blowing dust has been successfully reduced in the initial restoration area. Cattle grazing is now restricted on 3,000 acres, half of which has been restored.

Gaglio said grazing, monocrop agriculture and urban development are all “destroying” desert soils and unleashing more dust. To restore desert ecosystems and mitigate dust, communities and land managers need to change how water moves through the landscape, he said.

“Because we get so little rain, we must take care of every drop of rain we get and hold it on the landscape.”