The world of botany in the Big Bend is something like treasure hunting. I had a botanist friend who lived out here and would, at random, receive a message containing specific map coordinates — no names, no identifying information, just degrees sitting in one of those blank swaths of land that Google Maps doesn’t know what to do with.

He’d plug the coordinates into a navigation system and fling his truck towards a little dot on some wide open somewhere in the Trans-Pecos, upon which sat a rare plant: rare for its scarcity, for flowering at the time of year it did, for the fact that it was found somewhere unexpected.

The result of an expedition might be a clipping, which this particular botanist friend would, sometimes, deliver to a mysterious place in Alpine, Texas called The Herbarium.

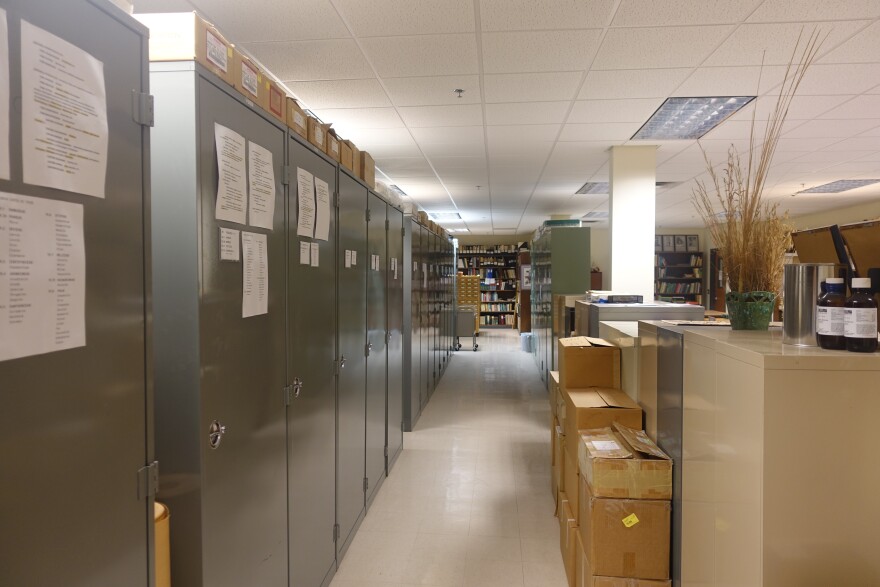

The Herbarium, to me, sounded something like Narnia — a mysterious door in the basement of an old science building on the Sul Ross State University campus, leading, somehow, to thousands of plant specimens from all over the Trans-Pecos region. A catalogue of the life found on our 19 million acres of desert grassland, scrub, salt basins, sand hills, rugged plateaus and wooded mountains.

The collected specimens are pressed, dried, mounted on papers, and filed into tall cabinets, tended to by two people my botanist friend would refer to as “The Elders” (very storybook indeed) — a retired botany professor and his wife, herself a former high school science teacher.

I finally visited The Herbarium this past Monday, descending the stairs of the Warnock Science building and heading into a room where I spotted the back of Dr. Michael Powell, his head bent over a microscope, meticulously moving tiny seeds onto a waiting notecard.

Powell is the Curator of the Sul Ross Herbarium, a position he’s held since 1979. He came to Sul Ross in the late 1950s to play baseball, but a botany class with Dr. Barton Warnock, for whom the building is named, quickly changed his course.

“You can combine your scientific interest with getting in the field,” he said. “Just think how neat that is: climbing mountains, camping in the wild and collecting plants.”

After leaving to get a masters in botany at UT Austin, Powell returned to Sul Ross to work as a professor, eventually taking on the herbarium curator role and co-authoring the definitive guide to Trans-Pecos plant life. “The interest never ends for me,” he told me. “I guess a lot of plant nerds are that way.”

Powell guided me over to a random cabinet and opened it to show me endless folders containing flattened and preserved Trans-Pecos plants — branches covered in crinkling flowers, furred leaves, spiny stems. There are specimens dating as far back as the late 1800s. Powell has collected many himself, along with his wife and field assistant, Shirley Powell.

For decades, the Powells have visited every ecosystem of the region to hunt for specimens for the herbarium: hiking mountains, traversing the desert, and camping in remote areas to collect new plants to mount and file away in the herbarium.

The Powells don’t work alone; the herbarium relies on a powerful team of plant-minded folks. Powell says the herbarium is, for the most part, a volunteer effort, aided by the botany students that come through the doors of the university. He estimates the effort has resulted in a collection of 100,000 specimens, making the Sul Ross herbarium the 4th largest in the state (out of 27 in Texas). And what’s done in the herbarium is not just the work of condensing myriad Trans-Pecos ecosystems into navigable cabinets, but condensing time itself — recording how our natural world has changed over the years, especially now, as climate change impacts the ways in which these plants are growing.

As a lover of archives, I was totally delighted. Being in the herbarium felt like being in the most fun and, dare I say, whimsical of archives, in which a record would correlate not to a book, but a literal piece of pressed life. Meandering the cabinets is like interacting with the wild world of the past.

I compared the herbarium to a library, and Dr. Powell concurred for the most part, but noted a key difference:

“ You could get rid of a book, wouldn't make any difference – maybe to the library, or to somebody, but it's not like this. This is a record you can't replace. Every single specimen is a record that can't be replaced.”

Each specimen is a timestamp of the moment in which it was collected. As Powell flips through a folder of specimens, and I see a range of collection dates: 1957, 1982, 2012. Each specimen is a specific historical record, revealing past plant distributions, documenting changes in species over time, and offering insights into plant morphology, genetics, and even interactions with other plant and animal life. And, herbariums help us look towards the future too, giving us the tools to identify newly discovered plants. Powell was actually instrumental in the identification of a recently discovered composite specimen, delightfully named the Wooly Devil, which made national news.

“We've had a bad two years 'cause of the drought,” said Powell. But he says and his wife Shirley are still out in the field a lot, doing the work, though the adventures may look a bit different these days. Less uphill meandering.

“I'm pretty close to the highways nowadays, “ said Powell, laughing a bit.

The highways, Powell says, are some of the most useful collection areas — that’s where the rain runoff goes — and also, these days, the most accessible. Most of the land in Texas is privately owned (about 93 percent).

“As a researcher, it's a problem,” says Powell. “It has been a problem forever… In the earlier days the ranchers were as interested as anybody else in what they have on their land. They were glad to have a botanist go on their land and take care of it.”

Powell says the Endangered Species Act turned the tides — while the ESA doesn't directly prohibit collecting endangered plants on private land, state law can override and limit the kind of access one has to plants. While access can be a problem, Powell clarifies that ranchers and other private land holders have played essential roles in plant species and ecosystem conservation, protecting the delicate ecosystems they have on their land through decades, if not centuries, of stewardship.

Powell walks me over to the area where they press the specimens: rectangular wood frames with old newspapers in between (The Big Bend Sentinel, specifically — Powell says that’s the only paper that’s the right size), bound tightly together, sitting over an incandescent bulb, flattening and drying out various specimens.

Powell opens a piece of newspaper, no larger than a pocket square, revealing a dime-sized flower, its petals a brilliant yolk-like yellow, carefully flattened. “ This is from a species that was never collected where this was found.” He’s clearly excited.

As we’re talking, Powell’s wife and field assistant, Shirley, comes in and takes a seat at a computer. She does all of the mounting at the herbarium.

“She won’t tell you, but it’s an artistic event,” said Powell. Shirley sort of waves him off. She’s being modest– the mounting is so clearly an art, arranging the specimens (which can come in all different sizes, or simply in pieces) on large sheets of cellulose paper, taking care to display all of their features, imagining how one may view them in the future.

Walking around the herbarium, I felt deeply moved by the work, the process of collecting, drying, gluing, and preserving. There’s a way in which it feels like many of the real parts of our world are slipping away — so much is virtual, digital, a scrum of pixels waiting to be snatched out of liminal space, the indefinite dark. The herbarium stunned me with its sheer tangibility. Paper, plants, timestamps from forever ago, captured and placed lightly atop one another in the sage green cabinets.

“Do you plan on doing this until the end of time?” I asked.

“Until I go away?” he asked. “Yeah, I do. As long as I can walk around. I just love what I'm doing and somebody needs to do it.”

It’s been raining in West Texas for the last month or so. Driving back to Marfa from the herbarium, I was surrounded entirely by green, like a giant shag rug had been thrown over the desert. It looked, suddenly, full of a different kind of opportunity. I imagined botanists ambling over the hills, hugging the highway, all hunting for specimens, capturing this precise moment in our world’s history.

All photos by Zoe Kurland.

This newsletter, and everything we do at Marfa Public Radio, is made possible by donations from readers and listeners. If you'd like to show your support for our work, become a member today.