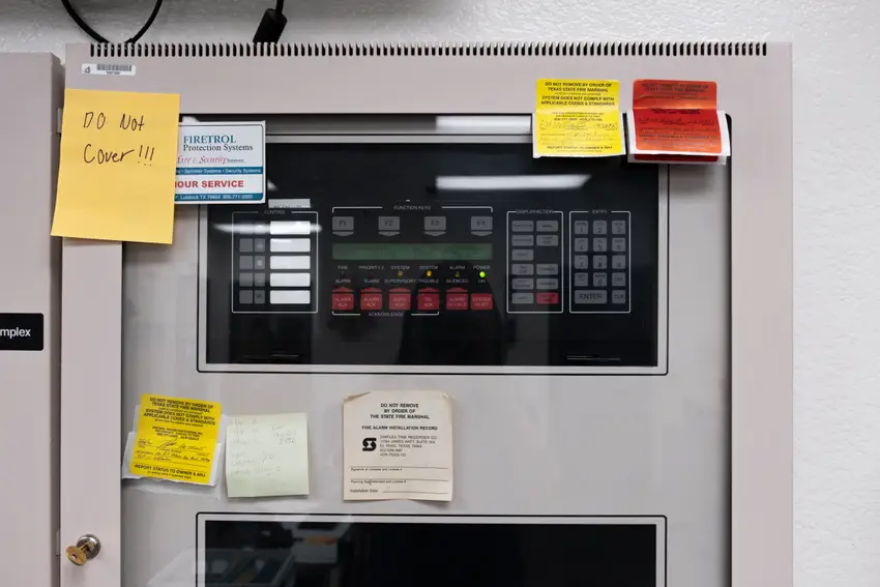

ALPINE — For the Alpine Independent School District, being $200,000 short of a balanced budget this school year meant dipping into its savings again. It meant one more year of using plywood sheets to separate classrooms in its elementary school and looking for cheap parts on eBay to fix the middle school’s aging fire alarm system.

The yawning gap between the money the small West Texas school district needs and the funds it gets could lead to bankruptcy in a few years, Superintendent Michelle Rinehart said.

“That math doesn't work out very well for us,” she said. “In terms of longevity, how long can you sustain that?”

Like most Texas school districts, Alpine ISD is facing critical operational challenges like stagnant student enrollment, rising operations costs and teacher shortages. But for Alpine and about 200 mostly rural districts, a kink in the state’s school funding system is worsening their financial troubles.

Whenever state and county officials disagree over local property value appraisals — which determine how much money schools should get from property taxes — school districts can end up with big holes in their budgets. It would cost the state about $700 million a year to fill those gaps in funding, said Josh Sanderson, deputy executive director of the Equity Center, which represents more than 600 school districts in the state.

The way Rinehart sees it, her district should have received about $1 million more in state funding this year. Not getting it was “a huge funding loss for us,” she said.

Lawmakers tried to temporarily address the issue during this year’s regular legislative session through an omnibus school finance proposal that would have given those school districts the money they’re missing. But the bill ultimately died as part of a dispute between the Texas Senate and House over whether to adopt a school voucher program. The session ended without a compromise on vouchers or new money for schools.

Gov. Greg Abbott is expected to call for a special session on education later this year, but it’s unclear whether helping these districts will be part of the agenda.

“It’s a problem that the Legislature could solve and only they can solve,” Rinehart said.

Texas’ pursuit of equitable school funding backfires

Texas guarantees every school district receives a certain amount of funding for each student they have, which is currently $6,160. Districts receive additional money if a student is bilingual, comes from a low-income family, attends special education classes or has certain other educational needs.

To cover their base budgets, districts are required to first raise the money through local property taxes. The state then gives school districts additional money based on the demographics of their student population.

The first step is for county appraisal districts to make an annual estimate of how much each property in school districts’ jurisdictions is worth. Property-owning Texans pay taxes based on the estimated value of their properties.

Most of those taxes usually go to pay for school districts’ maintenance and operation costs. The more money school districts get from property taxes, the smaller the state’s contribution will be, and vice versa.

But pinpointing the exact value of properties in a district is not an easy task — and problems arise when the state doesn’t agree with appraisal districts’ estimates.

At least once every two years, the Texas comptroller’s office is tasked with making its own determination about the total taxable value of properties within each school district. Then, as required by law, the Texas Education Agency uses the comptroller’s figure to calculate how much state money each school district is entitled to get.

The comptroller has been double-checking appraisal districts’ estimates since the 1970s to ensure that every school district gets a fair share of state funding. In the past, the comptroller’s office says, many county appraisers were valuing property under market value, leading some school districts to receive more state funding than they were supposed to. In some cases, property-rich school districts would get larger cuts of state funding than property-poor districts that needed the money more.

Now, the comptroller’s office says the vast majority of county appraisal districts are valuing property in their jurisdiction within market value, leading to a more equitable distribution of state funds.

But the state’s effort to provide more equitable funding has had the opposite effect for school districts like Alpine, where the comptroller’s office believes property values are higher than the local appraisal district does. It’s a lose-lose situation for school districts in those cases: School districts get less state funding because the comptroller’s office believes local property taxes will cover a larger portion of their budget — but they can only levy taxes based on appraisal districts’ lower property value estimates, so they actually get less money from property taxes.

Property value estimates from the comptroller’s office sometimes differ from county appraisal districts’ figures because the comptroller’s office usually determines property values a year after local appraisal districts do their evaluations, which can allow it to gather a more complete set of data.

Most of the school districts affected by this discrepancy in property value appraisals are in small, rural areas of the state. Sanderson, with the Equity Center, said he believes this is happening because appraisal districts in rural counties tend to have fewer resources to help them estimate property values accurately, and they might be more inclined to try keeping taxes low to appease property owners in their jurisdictions, who might be unused to the steep rises in property values as population growth and housing demand have gone up in recent years.

The state gives school districts a two-year grace period in which they can continue getting state funds based on the appraisal districts’ estimates before the TEA starts using the comptroller’s figures. But school districts like Alpine find themselves in trouble if appraisal districts don’t raise their property values closer to what the state believes they should be within that time.

Mounting needs, no new money

For Rinehart at Alpine ISD, getting that extra $1 million in state funding that her local appraisal district believes her schools should get would not only let her balance the school district’s budget — it would also leave her with an $800,000 surplus that could be used to raise teachers salaries for the first time in years and renovate the district's oldest campuses.

The district’s fuel, construction, health insurance and food service costs have steadily gone up in the last four years, Rinehart said. Students and teachers in the district’s single elementary school are still using decades-old books and furniture. The building doesn’t have a universal lock system and the key fob used to open doors doesn’t always work. Outside, the playground hasn’t been upgraded in years and it may need to shut down because the district can’t afford to put landing mats as required by state law.

Renovating the high school football field also weighs on Rinehart’s mind. The turf was installed more than 12 years ago and it’s starting to show signs of patchiness and looseness. These kinds of fields need maintenance every decade, she said.

Recent renovations have been financed through bonds, grants and donations. The school district built a new high school after a more than $20 million bond passed a couple years ago. The elementary school’s library is getting new carpet after a former student who owns a carpeting company gave the district a discount.

While bonds have helped address some funding woes, Rinehart said it would be a hard sell to ask taxpayers to put the district into debt once again after recently passing a multimillion-dollar bond.

Fort Davis ISD, located about 30 miles north of Alpine, has been passing deficit budgets for the last nine years. It started this school year with a $500,000 hole, and with just as much money left in the bank, Superintendent Graydon Hicks predicts the small district of fewer than 200 students will run out of money by next year.

Hicks has not given a pay raise to his teachers since 2019, and the district has been running on the minimum requirements needed to operate. It no longer has a cafeteria, or art or tech programs. Hicks said there is nothing left to cut.

In Orange Grove ISD, located about 40 miles west of Corpus Christi, Superintendent Eddie Hesseltine said his district faces the same issues. The district has had a budget deficit of $750,000 for the last two school years. Hesseltine calculates the district would have an extra $4.5 million a year if it weren’t for the difference between local and state property valuations.

Hesseltine said the situation is dire and the district could burn through its savings in the next couple of years. Substantial raises for teachers are also out of the question.

“Our people are professionals and they do a lot for our kids and I love to be able to give back but right now I'm just trying to keep the school running the day-to-day operations,” he said.

A looming special session

Abbott is expected to call lawmakers back to Austin in the upcoming months for a special session on education after one of his legislative priorities, school vouchers, didn’t get approved earlier this year.

Some legislators hope the special session will provide another chance to pass proposals public education advocates say are desperately needed, like raising teacher salaries and school funding to account for inflation.

But it’s unclear whether fixing the funding gaps created by the discrepancies between state and local appraisers’ property valuations will be part of the agenda.

Sanderson said the quickest solution would be for the state to simply cough up the cash.

“It’s really not new money that they’re giving those districts,” he said. “It’s just ensuring that those districts are getting what current law says they are entitled to.”

Rep. Gary VanDeaver, R-New Boston, a former superintendent of New Boston ISD, said the state’s efforts to make sure property values are appraised accurately help distribute state funds equitably among most school districts, but he acknowledged it’s also having unintended consequences for Alpine ISD and many other districts, including five in his rural East Texas region.

VanDeaver, a member of a special committee created by House Speaker Dade Phelan to recommend education proposals ahead of the special session, said he and several other lawmakers believe the issue needs to be addressed sooner than later. He said one possible solution could be to provide more data to local appraisal districts.

Brent South, chief appraiser for the Hunt County Appraisal District and chair of the legislative committee for the Texas Association of Appraisal Districts, said the more data that appraisal districts have, the more accurate their property valuations will be.

Getting property sales data would help, he said. In Texas, real estate agents are not required to provide sales data, something South said his organization has been advocating to change at the Legislature. But that will likely be a hard change to make.

“In Texas, we have such a high value on confidentiality, property rights and owner's rights to not have to disclose information to the government, and I get that,” South said.

Mary Lynn Pruneda, an education policy adviser for the public policy think tank Texas 2036, said lawmakers have a chance to tackle the property valuation discrepancies in the upcoming months.

“In crafting solutions to the problem, the state has to walk a fine line. Balancing the tensions between maintaining accurate property valuations and ensuring that districts aren’t harmed by under- or over-appraisal is a difficult one and will be the focus of much conversation this special session,” she said.

Worries also remain that the debate over school vouchers could either pull attention away from funding concerns or hold any new money hostage to the approval of a voucher program.

“How are we even talking about vouchers when we have districts like ours that aren't even receiving their full allotment?” Rinehart said. “We should be fixing that first.”