This article originally appeared on Inside Climate News, a nonprofit, non-partisan news organization that covers climate, energy and the environment. Sign up for their newsletter here.

REDFORD, Texas—Plans for a border wall through the Big Bend region of West Texas are raising alarms among residents and elected officials.

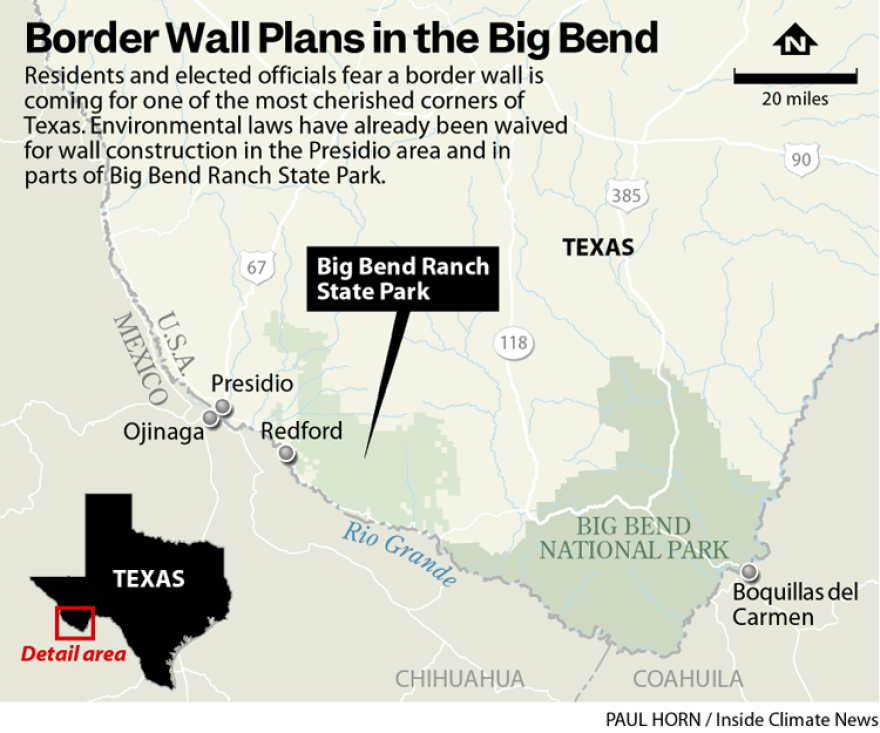

U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) intends to build border barriers throughout this remote region of Texas that encompasses ranchland, small towns and a cherished state and national park.

Last week, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) waived 28 laws for environmental protection and historical and archeological preservation to expedite construction in a more than 150-mile stretch from Fort Quitman in Hudspeth County to Colorado Canyon in Big Bend Ranch State Park. An online map posted by CBP indicates that “smart wall” construction is planned both within the state park and in neighboring Big Bend National Park.

Historically, the number of people crossing unauthorized into the United States in the Big Bend region is much lower than in more urban, populous areas. But since the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, passed in July 2025, appropriated $46.5 billion for border wall construction, no region appears to be spared.

While unauthorized border crossings have dropped dramatically in the past two years, the Trump administration is moving forward with the border wall, including in Arizona’s San Rafael Valley and wildlife refuges in South Texas.

According to the CBP website, construction for the smart wall can include a steel bollard wall or waterborne barrier, “along with roads, detection technology, cameras and lighting and in some cases a secondary wall.”

The Big Bend region in southwest Texas may be next. In Presidio County, the Big Bend Sentinel reported that landowners have been approached about leasing for barrier construction. Marfa Public Radio reported that companies are looking for land for staging areas.

The highest elected official for Brewster County, Judge Greg Henington, spoke against the wall during a public appearance in the county seat of Alpine on Feb. 12. Big Bend National Park is in Brewster County.

“This county judge sees no reason to go with a border wall in Brewster County,” Henington, a Republican, said. “I get border security, but there are other ways to do it.”

David Keller, a noted archaeologist of the region, characterized the plans for border barriers in the Big Bend as “the military industrialization of one of the last, great, unspoiled places remaining in the United States of America.”

“One of our most beloved national parks and our state’s largest park will be scarred beyond repair,” he said.

A CBP spokesperson said that the entire 517-mile stretch of its sector’s border with Mexico is scheduled to receive new infrastructure or upgrades. “This scope includes areas within Big Bend Ranch State Park and Big Bend National Park,” the spokesperson said. “Depending on terrain and operational requirements, each area may receive any combination of barrier installation, technology deployment, and road improvements. Contracts for these projects are expected to be awarded in the coming weeks and months, with various phases of construction anticipated to commence toward the end of the year, upon completion of land acquisition, and continue over several years.”

U.S. Rep.Tony Gonzales, a Republican who represents Texas’ 23rd district, which includes the Big Bend area, did not respond to a request for comment.

CBP has offered little public information about border barrier construction in the Big Bend. But word spreads quickly in the region’s closely knit communities. During a conference last week in Alpine focused on water issues, attendees peppered speakers with questions about the wall.

Hudspeth County Judge Joanna MacKenzie, a Republican, said during the event she is opposed to wall construction in her rural county. “It’s a bandaid to make people feel better who don’t live here and don’t see it,” she said.

Hudspeth County has roughly 100 miles of border with Mexico along the “Forgotten Reach” of the Rio Grande. To the southeast is Presidio County, where the only existing border barrier is recently installed concertina wire in the city of Presidio at its border crossing with Ojinaga, Mexico. Presidio County Judge Joe Portillo has said that alternatives to a physical wall should be explored.

The Rio Grande and the Rio Conchos, which flows north from Mexico, converge at Presidio. The area, known as La Junta de los Rios, has a rich Indigenous history.

Keller, the archaeologist, said the proposed border wall would destroy thousands of years of Native American history stored in the soils around La Junta de los Rios. Among the laws waived by DHS were the Archaeological and Historic Preservation Act and the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act.

DHS issued the waivers to expedite construction through Hudspeth and Presidio counties on Feb. 13. The order, signed by Secretary Kristi Noem, called the Big Bend Sector “an area of high illegal entry where illegal aliens regularly attempt to enter the United States and smuggle illicit drugs.”

Charlie Angell, a resident of Redford in Presidio County, argues otherwise. He said in more than a decade owning property on the Rio Grande, he has never seen anyone enter illegally on his land. He said he will refuse to sell his property, which includes his residence some 250 feet from the river.

“I plan to live here the rest of my life,” he said. “I don’t want to start over.”

Through his company Angell Expeditions, he has taken thousands of people on river trips on the Rio Grande. He said the river attracts wildlife—javelinas, foxes, bobcats—out of the surrounding desert seeking water. The wall could cut them off, too. Angell’s property also includes the El Polvo archaeological site, which would be impacted by any construction.

Just downstream of Angell’s property, Big Bend Ranch State Park offers 300,000 acres of rugged desert expanses for hikers and mountain bikers and Rio Grande access for paddlers. CBP’s map indicates border barrier construction from the western edge of the park to Colorado Canyon, a common starting point for paddling trips. The map shows the barrier picking back up again further southeast in the park and passing through the town of Lajitas.

“The Texas Parks and Wildlife Department has not received a request from the federal government for any border-barrier infrastructure within Big Bend Ranch State Park,” said spokesperson Stephanie Garcia.

Big Bend National Park lies southeast of the state park. The world-renowned national park draws visitors to explore the Rio Grande, hike the Chisos Mountains, observe wildlife and experience some of the darkest skies in the continent. Despite its remote location, more than 500,000 people visit the park every year. The National Park Service estimates the park contributed $56.8 million to the local economy in 2024.

Over the weekend, CBP updated its online map to show plans for smart wall construction within Big Bend National Park. Previously, the map had indicated “detection technology” would be used within the national park.

The area now highlighted for smart wall construction begins at Santa Elena Canyon and continues along the river until Mariscal Canyon. The map then shows the smart wall continuing on the other side of the canyon to the Hot Springs, through the Rio Grande Village campground and Boquillas border crossing, stopping at the entrance to Boquillas Canyon.

“We have no knowledge of any plans for a border wall,” said Don Corrick, the spokesperson for Big Bend National Park, on Friday. National Park Service headquarters did not respond to a request for comment.

“So Far From Everything”

Lilia Falcon is a lifelong resident of Boquillas del Carmen, a small town overlooking the Rio Grande within Mexico’s Maderas del Carmen Natural Reserve. The only legal border crossing between the United States and Mexico in Big Bend is at Boquillas.

On Feb. 14, dozens of visitors tramped down the dirt road to the river crossing, shelling out $5 each to be guided across. Many of them ended up at José Falcon’s Restaurant overlooking the river, eating enchiladas and drinking Mexican beer.

Lilia Falcon now runs the restaurant founded by her father José in 1973. She said that people in Boquillas are opposed to a wall.

“We have always said we have our own beautiful, natural walls: the canyons,” she said while taking a break from working the restaurant’s cash register.

Sheer rock canyons rise above the Rio Grande both upstream and downstream of Boquillas. The community is three hours by road to the nearest sizable town in Coahuila. Falcon said its remoteness has always deterred people from attempting to cross unauthorized into Texas.

“We are so far from everything,” she said. “Big Bend has always been very protected.”

On the U.S. side of the border, nearly 100 miles of rugged parkland and a Border Patrol checkpoint separate any potential border crossers from the closest U.S. town to the north. Border Patrol also operates within the park.

Falcon said wildlife would suffer if a border barrier is built. She pointed out that the black bears now living in Big Bend crossed into the park from Mexico. Falcon also worries that flooding could damage or wash away any border infrastructure installed along the river.

During the first Trump administration, women in Boquillas embroidered messages against the wall on handicrafts. Tourists could pick up handmade koozies or tortilla warmers with anti-wall slogans. A bumper sticker reading “No Al Muro” still adorns a minifridge at the restaurant.

Falcon said they may start embroidering “No Al Muro” once again.